Ancient Egyptian Pigment Reveals Latent Prints in the Near-Infrared

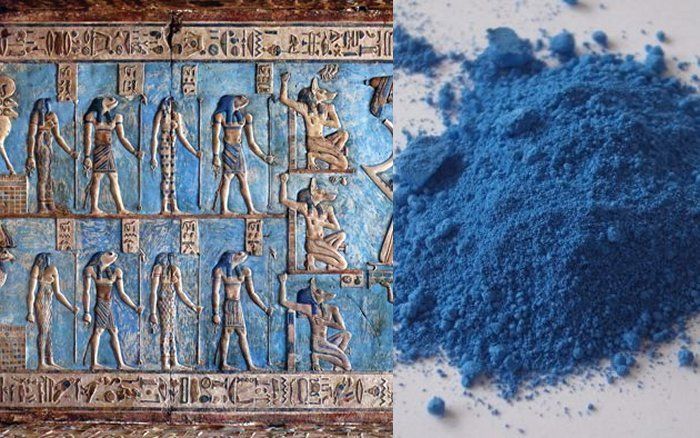

Egyptian blue is the world’s first known synthetic pigment, used for thousands of years until the ancient recipe was lost after the fall of the Roman Empire. Now, researchers are recreating the pigment, and using its unique properties to help solve modern day crime.

A team from Curtin University in Australia have demonstrated that the pigment actually glows in the near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, which can be extremely helpful to investigators pulling latent prints from shiny or patterned materials.

“The most common approach to detecting latent fingerprints has been the use of dusting powders made from white, black or fluorescent powders,” said Forensic Chemistry professor Simon Lewis, in a statement provided by the university. “However, there remain many highly patterned and/or reflective surfaces that continue to prove troublesome, making it hard to see fingerprints.”

Researchers first crushed, or micronized, the pigment into a fine powder, and dusted for prints. They then used a white-light source to illuminate the surface, and a digital camera to photograph the prints. According to the researchers, the Egyptian blue powder outperformed commercially available dusting powders on patterned and reflective surfaces.Dr. Gregory Smith, a fellow researcher on the project, has used near-infrared imaging to find Egyptian blue pigment on millennia-old Egyptian artifacts for more than a decade.

“I’d always wanted to investigate Egyptian blue for fingerprints because it exhibits strong photoluminescence in the NIR region,” he said. “It’s also non-hazardous and very stable, with painted artefacts dating back several thousand years still showing strong NIR luminescence.”

Also known as cuprorivaite, the pigment is made up of roughly 65 percent silica, 15 percent calcium oxide, and 20 percent copper oxide. The first recorded preparation of the pigment was before 3,200 B.C., according to researchers, and was used throughout the ancient world until the beginnings of the Dark Ages.

“The secret of how to make it was lost after the Roman Period, but then rediscovered in the 19th Century,” Dr Smith said in a press release.

The team said the technique is a safe and simple way to image latent prints, and can also be extremely cost effective. What has made the pigment so vivid and durable over so many thousands of years, also makes it very useful to modern day investigators.

The study, “ Micronised Egyptian blue pigment: A novel near-infrared luminescent fingerprint dusting powder

,” was published in the journal Dyes and Pigments.

SOURCE

ForensicsMag